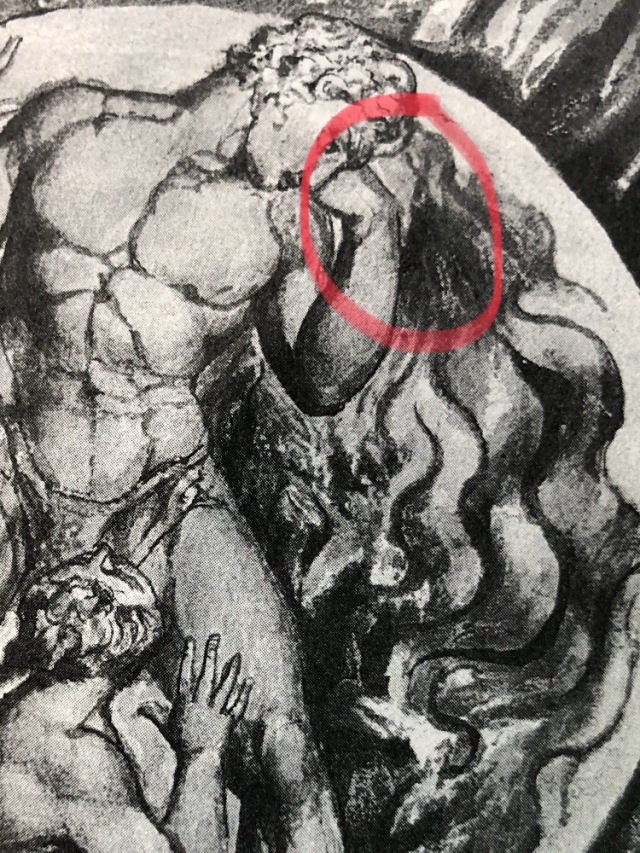

The engraving from William Blake’s Plate 49 depicting Los engaged in sodomy is a non-secular subject in which Blake explicitly alludes to (but does not name) the tyrannical government in power- most likely of Napoleon’s, but openly assigned to treat authorities such as our current Trump presidency. Along with the anthropocentric charges, “Who creeps into State Government like a catterpiller to destroy,” (Blake 202) this is the first time he directly compares beasts to the government, unambiguously describing the animal-like phenomenological action of “creeping,” and introducing simile structured against the sentence object, “to destroy.” Blake introduces Los as apparently being fellated by the authorial self. The editorial footnote describes Blake’s own transgressing images from Milton Book I to Book II, which is an interesting digression due to not only Blake’s own presence in the story, but also because the content of his process- on being destroyed ironically from one book to become part of the sequence or essence of another. Another detail that seemed out of place was the background of Plate 47 in which a woman with big, wavy, hair surrounds Los, within the circumference of his halo. Is Oothoon gazing upon the male bodies performing, perhaps for erotic desires?

Los’s left arm curls back into a thinking position, his hand covering Oothoon’s face. This relates to Los’ love for revolution, “To cast off Bacon, Locke & Newton from Albion’s covering […] To cast aside from Poetry, all that is not Inspiration,” (202). Both Los and Oothoon are juxtaposed versus the Enlightenment thinkers, and described much in the same way Blake has chosen to draw her, as requiring a deconstructing of layers in order to see her, to “cast off,” the hand of Los, and while Blake’s conventional critique of Royal Academy influencers and thinkers of the French Revolution, in consideration of his previous demonizations of regicide and anthropomorphic metaphors about both the Church and State, is not presented here in the usual compartmentalization by images of war and in descriptions of cosmic connections between Los, the author and the various geographic pinpoints to retell Blake’s dreamlike vision of how “Before Ololon Milton stood & perceivd the Eternal Form,” (Blake 200), other relativism to Milton and Blake’s allegorical characters represent London’s existence and subtending, religious themes which form the plot-like conventions of systemic storybuilding. The plates enabled for Blake a mimetic exploration, and thus the ultimate nationalistic gesture in which he envokes “Inspiration” with a capital ‘I,’ alongside traditional, religious imagery, while drawing this Inspiration to visually depict males performing oral sex acts in conjunction with the “State Government,” (202) and explicitly actualizes a metaphysical, self-annhilation using homoerotic imagery that evokes Milton’s biographical trials and the sense of Los’ war in Jerusalem, while simultaneously persuading the more abstract and conscious limits of his (French) reader’s political and social perceptions with an overtly associated logos of symbolic, non-fertile sexual intercourse. The images falling under Victorian censorship need to be re-examined, including Oothoon’s overlooked, feminine presence. It is said that ‘the devil is in the details,’ where does Milton lie in this engraving of Blake’s threesome with Los and Oothoon? The males in Plate 49 are being subjected to the matriarchal gazing which satirizes Europe’s war with Jerusalem, and under the shadows of Beulah, subjects Blake to not only fellatiating Los himself/a simulation of Blake’s political imagination/America’s own prophet, but also to the actual treatment of readership for his representing in negative connatations the personal notions of liberty through pubically demonstrated symbolic gestures, generally thought not to be displayed in either religious or political institutions. Blake’s genius is sensuous, and not to be confounded by the devout, religious practices which frequently swayed inspiration for the author in the eighteenth century.

-Bradley Dexter Christian